Welcome to Splitsville: How Reno Became the Divorce Capital of the World

For decades the city was the place to break your marriage, and pick up the pieces.

A picturesque, scattershot tableau of whitewashed buildings against sprawling, dusty Nevada mountains, Tule Springs Ranch in Floyd Lamb State Park could easily be mistaken for an abandoned Western movie set. Just 20 miles from the glitz of the Las Vegas strip, it feels like a world away. Fowl-filled ponds have replaced the bubbling natural springs that once satiated Ice Age beings (Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument is a couple miles north). Peacocks fan out around the lush grounds. There’s a historic white bridge, a defunct water wheel, and a water tower jutting to the sky.

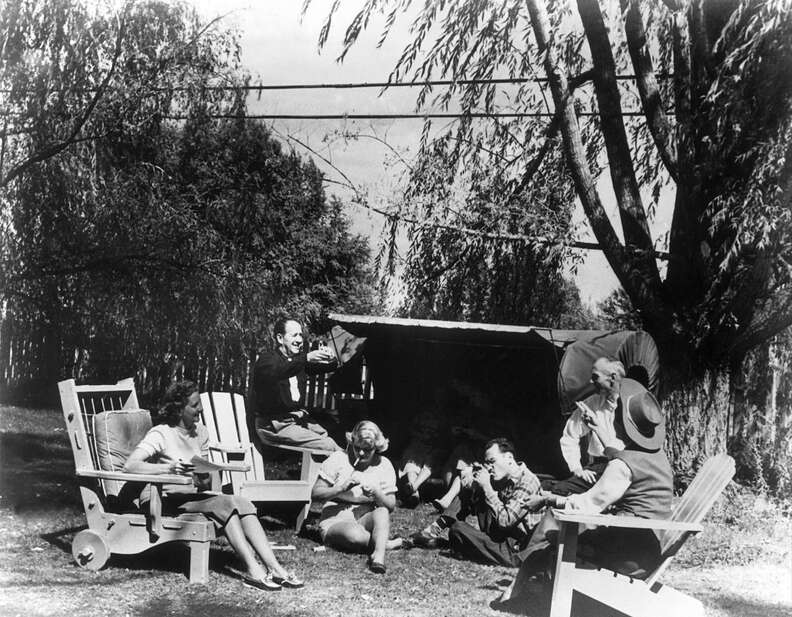

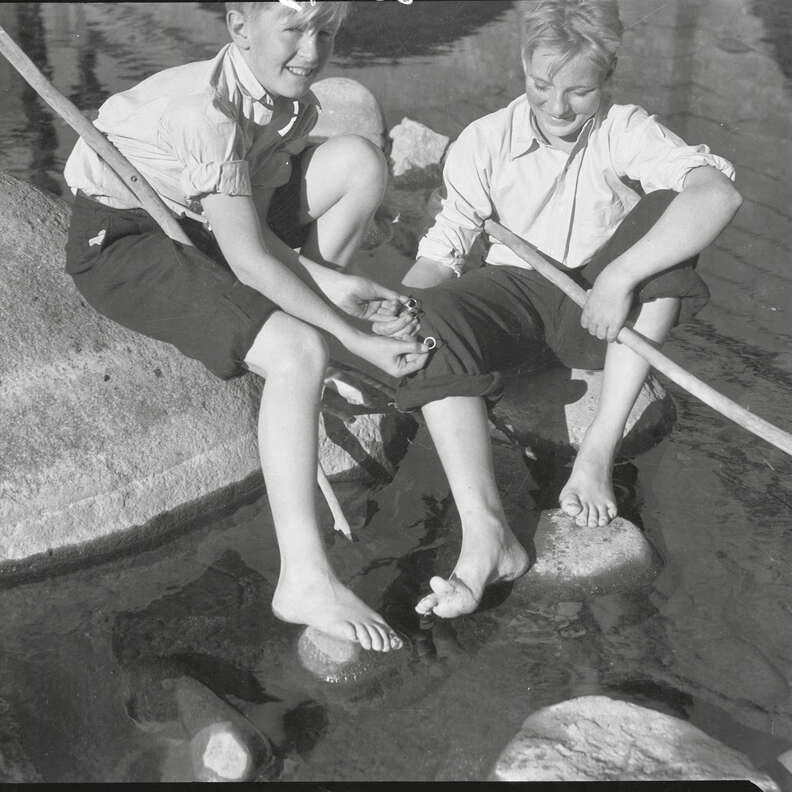

And to say it's out of central casting wouldn’t be far off from its actual origins. In its 1940s heyday, Tule Springs served as a dude ranch—in this particular case, a working ranch converted to accept “dudes,” or outsider male and female tourists, who wanted to, for lack of a better term, cosplay Western life. An empty shell of itself today, back then it bustled with strapping ranch hands tending to livestock and guiding guests in the way of the cowboy. Fish-out-of-water clients mostly came from big cities back East to play out their countryside fantasies: going fishing, attending rodeos, riding horses, splashing in ponds. Shooting trap. And eating copious amounts of red meat.

About 15 miles south in Lorenzi Park, you’ll find another set of abandoned lodgings, this time cloaked in a more rustic brown hue. It’s the remnants of Twin Lakes Lodge, another dude ranch dating to the 1940s. With two man-made lakes, islands, and green tree groves, Twin Lakes offered a more slick resort vibe, even more so now that the trees have been replaced with lanky palms reaching skywards. All the better to draw starlet clientele.

And for these two ranches, they were mostly women clientele. Because while the remnants of the two ranches look vastly different, they had one major thing in common: They both served as “divorce ranches,” a key player in Nevada’s once-thriving divorce industry. For decades, legally married women from other states would check in and, six weeks later, check out—one spouse lighter.

Accidental Progressives

In the late 19th and early 20th century, divorce was still largely taboo in much of the United States. Couples that wanted to split had bleak options. In states like New York, for example, the only way to get a divorce—up until the 1960s!—was to prove adultery. Reasons like spousal abuse or simple mutual consensus didn’t even figure in the equation. (Because of this salacious reasoning, divorces in New York were usually splashy tabloid affairs, and courtroom trials became public entertainment. Seems like they didn’t have much else to do back then.) The plaintiff also had to wait a painful year after filing their paperwork before a divorce would be granted.

A few states with more lenient policies sprung up as “divorce mills,” places where one half of the couple could set up residence relatively quickly and split from their spouse on less stringent grounds. As men were the majority of the workforce, residency duties usually fell to the wife. Utah, South Dakota, and Indiana were all places they could do the deed.

But none of those states could hold a candle to good ol’ Nevada, entrepreneurial and strategic from the beginning, and liberal as a matter of necessity. When the Silver State was established in 1864, the residency requirements to enjoy such benefits as voting and filing legal suits—especially divorce suits—was just six months. It had to be brief: The population of Western boomtowns were transient by nature.

But on top of that, the grounds for divorce had wide berth, and included the catchall of “extreme physical or mental cruelty” within either party, typically presented to be of a mental nature. It was acceptable to prove that the defendant had been unkind, stayed out late, or caused the plaintiff enough distress to disrupt their life. In some cases, it saved women from dangerously abusive relationships. Others were ruled on more frivolous grounds like, say, a husband refusing to let his wife listen to the radio in the house. (Get rid of him, we say.)

By 1909, Reno, Nevada’s most built-up town, had already gained a reputation as a go-to for a quickie divorce. A very specific industry sprung up, with lodging and entertainment proliferating within steps of the Washoe County Courthouse. Divorce tourism bloomed: The bridge a block from the courthouse steps became known as the "Wedding Ring Bridge," where the newly divorced would dramatically toss their wedding rings (or a cheap ring they bought at the local Five and Dime) into the Truckee River. Famous actresses like Mary Pickford had come for a divorce, and with them, the eyes of the world. Their experiences even made it on stage—playwright and congresswoman Clare Booth would later write the comedy The Women about her 1929 stay.

In 1927, the residency requirement was reduced to three months. And after the Great Depression decimated domestic industry, the 1931 Nevada legislature passed two crucial economically driven bills that would end up forever changing the state’s fortune. The first legalized gambling. And the second upped the total grounds for divorce to nine, and reduced the residency requirement from three months to just six weeks.

“The Reno Cure”

Reno’s divorce industry was off to the races. With more people able to afford a six week sojourn, the divorce business ramped up from busy to booming. The city gained a reputation as the “divorce capital of the world” with visitors coming to “take the six-week cure.” Tabloid writer Walter Winchell nicknamed the process the “Reno-vation.” The women—and men, and at least one a foreign dignitary—arrived in droves: by air, by car, and by train. The Overland Limited that pulled into Reno was dubbed divorcée special. Over 325,000 marriages would come to an end in Nevada during that time.

And while they may have been there for different reasons, all those people desperate to return to single life had one thing in common: They needed somewhere to stay for six weeks, complete with a housing manager willing to testify that you hadn’t left the state for over 24 hours in that time. You could choose to bunk in a boarding house, often with a roommate. Some women brought their kids and took jobs cleaning or working as “shills” in casinos (AKA posing as decoy customers to get people to participate). But if you had some cash and an appetite for adventure—or, at least, some rugged cowboys—you could ditch your pearls for jeans and cowboy boots, and shack up at a divorce ranch.

Some ranches were more modest, with rooms not much more than a bare-bones cabin. And others, like the luxurious Flying M E Ranch favored by the Hollywood elite, offered individual tanning beds, all the better to return home single and fabulous. The more high-end ranches employed cowboys to lead group activities and provide entertainment. And in some instances, the hunky stockmen themselves were the entertainment. (The Lazy M E Ranch, located just south of Reno, earned itself the nickname the “Lay Me Easy”.)

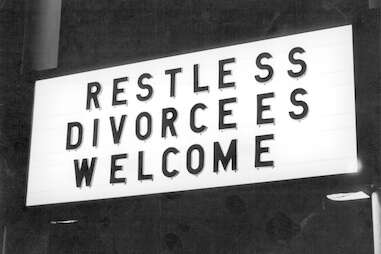

The ranches also provided psychological comfort, fostering a community of sorts that implicitly understood the stresses and pressures of the situation. One visitor recalls being afraid her whole stay, worried that her husband would show up and contest the marriage, but ultimately comforted by welcoming nature of the ranch (and by a cheeky sign that said 'Welcome, Divorcées'). Lifelong friendships were forged, and, considering the circumstances, it’s not surprising that Reno gave way to a thriving lesbian scene, as memorialized in filmmaker Donna Deitch’s groundbreaking 1985 cult hit, Desert Hearts.

Reno enjoyed the fruits of the divorce-seekers wallets, and in turn, the women got a taste for what it was like to be unhitched in a frontier pocket that was morally… let’s just say, flexible. They got babysitters for their kids and went out on the town. They danced, flirted and had affairs, gambled and went to taverns unaccompanied. The rest of the country looked in through pulp novels with titles like Reno Rendezvous and titillating magazine articles like "My Dude Ranch Love Affair," published in a 1938 issue of True Confessions.

For some divorce-seekers, it was a time to free themselves of the bounds of marriage once and for all. Others came with “spares,” or men that they would marry as soon as their marriage was severed. And some would pick up a new beau along the way. There’s even one account of a woman turning right around and marrying her divorce attorney.

Las Vegas gets in on the action

But Reno was about to have some competition. In 1931, Las Vegas was still a sleepy village of about 5,000, but with the launch of the Boulder Dam (now the Hoover Dam), workers quickly swelled the population to about 25,000. And though the city still lacked a decent hospital (that could come a few months later, thanks to injuries sustained at the dam), visitors to Las Vegas could now gamble to their hearts’ content—in fact, the first gaming license in all of Nevada was given to Mayme Stocker at Vegas’ Northern Club.

Slots-hungry tourists flooded into Vegas from Los Angeles, but Reno still had the monopoly on the divorce crowd. In an attempt to get their hands on a piece of their sister city’s economic goldmine, they did what Vegas is so well known for today: They kicked off a celebrity residency.

In 1939, Ria Langham was a wealthy socialite with a thing for actors, married to up-and-coming heartthrob Clark Gable. She was on her fourth marriage, him, his second. But though she played a major part in elevating his public profile (not to mention wardrobe and grooming habits), the union was somewhat one-sided. Gable was often seen stepping out on the town with his female co-stars, with many a dalliance swept under the rug. That was, until he met comedienne and Hollywood darling Carole Lombard on the set of 1932's No Man of Her Own.

The pair didn’t start dating until four years later, while Gable and Langham were separated, and though they kept the relationship secret, they were often spotted out on the town. To make matters worse for Langham, the press applauded and encouraged—dare we say, shipped—the adulterous affair, informing the court of public opinion. Suddenly, Langham was characterized as the one standing in the way of Gable’s happiness.

While she originally planned to give Gable a long, drawn-out California divorce, perhaps to save face, Langham opted for a quickie split in Nevada while Gable was busy filming Gone With the Wind. In a masterful twist she struck a deal with the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce: In exchange for six weeks left alone, she would control her own narrative with a splashy spread in the Las Vegas Review-Journal. She paddled around Lake Mead and gambled. She gave sound bites about Gable. She told the paper Vegas had been “the finest and shortest vacation I ever had in my life.”

Las Vegas’ divorce racket was all systems go, and the addition of the Vegas strip in 1940 added more shine to the city's lawless veneer. Soon, Las Vegas divorce ranches like Tule Springs and Lorenzo Park were just as swarmed as Reno’s divorce ranches. Other celebrities came to avail themselves of their services, like Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs. Liz Taylor posted up at a ranch while waiting out Eddie Fisher’s divorce (conveniently, he was doing a residency at the Tropicana at the time).

Of course, the industry began to decline when the rest of the nation caught up. In 1970, California governor Ronald Regan, a divorced man himself, signed into law the nation’s first no-fault divorce bill, granting couples the opportunity to split up without placing blame. Other states quickly followed suit.

And while the divorce ranches have since disappeared, one major side effect of the industry still remains. When quickie divorces were followed shortly after by shotgun weddings, the newly single almost-newlyweds needed somewhere to secure their impending nuptials. In short order, wedding chapels took over Las Vegas, and eventually the city traded its reputation for speedy divorces for one of quickfire matrimony (we see you, Bennifer). Often, with Elvis in the building.

As for the rest of Nevada, they’ll always have gambling—whether for love or money.