The Hidden His-and-Hers Masterpieces of Rural Utah

Admission is free, but you will need a full tank of gas and four-wheel drive.

In the most famous pictures of Robert Smithson’s monumental earthwork “Spiral Jetty”, the craggy coil of black basalt and limestone protrudes through the surface of the Great Salt Lake. In many of these photos, the lake takes on a deep red hue thanks to the local plankton. In others, it looks more like a fogged-over mirror after a hot shower. I’d seen both versions during slideshows in undergraduate art history classes, and that’s how I’d pictured it ever since.

Parked at an I-80 rest stop, I did a quick Google search for precise directions and incidentally discovered my mental images of the waterlogged work were no longer accurate. Apparently, "Spiral Jetty" had dried out, left to bake on the shore as prolonged drought forced the lake to recede. But I didn’t care. After years of shouldering my way through the museums of the world, taking an elbow to the ribs in front of Manet’s "Olympia" and an accidental uppercut at the Sistine Chapel, I was in search of, if not artistic solitude, then at least an art experience marginally more contemplative than Wrestlemania. If that took driving hundreds of miles to and through the salt flats of northwest Utah in the midsummer heat, then so be it.

First some backstory: Beginning in the 1960s, a group of primarily American artists frustrated with the commercialism, stagnation, and insularity of the art world decided to make artworks in and of the natural landscape. The movement was called Land art, and among its proponents were a couple named Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt, who were first introduced while the former was tripping on peyote.

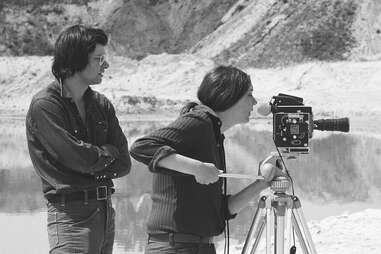

After marrying in 1963, the pair traveled extensively through the American West scouting sites where Smithson—who once compared museum galleries to “asylums and jails”—could create freely. A 1968 trip through the Nevada desert was revelatory for Holt, who later recalled it as “an overwhelming experience of my inner landscape and the outer landscape being identical.” The two were creative partners from the start. Together they parodied bicoastal art world attitudes in short films and purchased a tiny island off the coast of Maine purely for art’s sake. Holt helped document the construction of "Spiral Jetty" in April 1970, capturing lighter moments (like Smithson stepping in a tar seep) amidst the otherwise heady artistic process; Smithson was by Holt’s side as she made her own nature-centric artworks in rural Montana and the woods of Dartmoor National Park in England.

And then, while scouting a site for a new earthwork in July 1973, Smithson was killed in a plane crash over Amarillo, Texas. The grieving Holt completed his planned—and inadvertently final—earthwork, then threw herself into the project that would become "Sun Tunnels."

She crossed Arizona and New Mexico in search of the perfect location, only to eventually find the ideal site back in northwest Utah, just 100 miles west of "Spiral Jetty."

Taken together, "Sun Tunnels" and "Spiral Jetty" constitute a love story. And seeing them might be the least commercial art experience in the US. There are no gift shops, no entry fees, no parking structures, and no nearby attractions. As it turned out, the remote location is itself an extreme if effective form of crowd control. It practically forces you to contemplate the artworks, but also the planet, the sun, geologic time, and yourself.

Smithson and Holt understood the power not just of a vast landscape but of this particular stretch of vast landscape in Utah. I figured that whatever they saw in it was unlikely to have been swept away by receding water levels alone. Undeterred by my earlier Googling, I forged on to see for myself.

Nothing lining the two-lane road to "Spiral Jetty" screams high art. There are fields of solar panels and a semi-obscured industrial plant with a sign touting it as a NASA equipment supplier. Turning off the main road, I passed a lodge with two locomotive engines parked out back, built to commemorate the nearby completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Here the road turned to gravel, and 15 miles later it dead-ended into a dirt lot. Down a rocky slope at the lot’s edge: the stem of a 1,500-foot coil, bone dry as promised.

A white pickup truck rolled in behind me, out of which emerged a man and woman. They walked down the slope and over the dry bank to the water’s edge, then turned around, got back into their truck, and left. I wondered if I had just been privy to a creative if slightly ill-advised date. Despite the indisputable role Holt and Smithson’s creatively fertile marriage played in his planning and construction of the earthwork, absolutely nothing about "Spiral Jetty" or the surrounding landscape suggests romance.

It does, however, feel borderline apocalyptic and acutely uninhabitable. In the heat, the mountains on the opposite shore appear to tremble and hover slightly over the lake’s surface. There is no fresh water, no shelter, and precious few signs of life. A few white birds hang on the wind overhead. Underfoot, the occasional dead moth, glazed over with salt and embedded in the slushy pink shoreline.

I walked along the edge of the spiral, which has a meditative effect but not a comforting one. When Smithson’s sometimes gallerist (and heiress to the 3M fortune) Virginia Dwan visited the work, she called it “infernal,” and she was right: there is something sinister about the size and setting of "Jetty." Its recent desertification only heightens this impression. Smithson intended "Spiral Jetty" to meld with the lake and the landscape, and for several years it was completely submerged. Its exposure serves as an unconventional barometer of climate change and agriculture’s catastrophic effect on the lake, which hit a record low water level in 2022 and will fall three feet this summer alone. One Utah lawmaker called its ongoing depletion “an environmental nuclear bomb.”

Rather than endeavor to see both earthworks in one day, I made my way to a motel in Wendover, a small Utah town (population: 1,135) situated on the Nevada border. It’s easy to tell where Utah ends and Nevada begins, what with the front door of multiple casinos sitting spitting distance from the state line. And if that isn’t indication enough, there’s also “Wendover Will,” the 63-foot tall neon cowboy who winks while welcoming you to the town of which he’s a namesake.

Rather than lose my gas money at a blackjack table, I filled my tank on the Utah side and took the I-80 exit for the Bonneville Salt Flats Speedway. I followed the unpaved track of TL Bar Ranch Road for the better part of two-and-a-half hours, inching ahead for the sake of the car’s shocks, the birds springing out of the bushes unnervingly close to the windshield, and the rabbits and mice darting across the dirt road. An abandoned red car at the roadside had clearly been used as target practice by rowdier caravans. A tumbleweed bounced lazily nearby, completing the picture. When I finally arrived at Holt’s 40-acre plot in the Great Basin Desert, I found what I’d searched for: total art-adjacent solitude.

Consisting of four 22-ton, 18-foot-long concrete tunnels set in an ‘X’ formation and aligned with the sunrise and sunset on the solstices, "Sun Tunnels" took three years, a full construction crew, two engineers, an astrophysicist, and an astronomer to complete. It’s famously breathtaking when aligned with the sunrise and sunset of the solstices, but beautiful anytime the sun shines through the tunnel ends and the holes cut into the sides. Light and shadow changes shape in tandem with the turning earth, bringing into focus the fundamentally primordial connection between time and light.

But with the afternoon sliding into dusk, I was taken by other elements: the low hum from the wind blowing through the tubes, how the work framed the surrounding mountains and desert, and the unexpectedly pleasant shelter it provided.. It actually seemed antithetical to "Spiral Jetty," which left me feeling self-consciously mortal and exposed. Standing at the axis of the four tunnels anchored me physically and mentally. It felt like being alone with the base elements of life on earth: time, light, air, and space. Holt meant for this to happen: “The center of the work becomes the center of the world,” she wrote in the accompanying essay for the April 1977 issue of ARTFORUM. On the way out, I encountered a single Union Pacific truck, and pulled over to let it pass. The driver double-tapped his brake lights in thanks.

By the time I made it back to Wendover, darkness had long since fallen and any local restaurant not located inside a casino had closed. I laid in bed and perused the "Sun Tunnels" geotag on Instagram, scrolling through photos of the gatherings that take place on the solstices, of people posing together in and on the tunnels, and of nighttime shadow-casting excursions using colored flashlights. Here was evidence that other people had made this same pilgrimage before me, and done it in groups, on dirtbikes, or with an acoustic guitar in tow. And even I, who’d particularly relished my solitude there in an art-flavored bout of misanthropy, had to admit experiencing this art together looked like a nice time.